Alt Investments

Hunting Private Equity Opportunities In Stressed Times

This news service looks at private equity and related private markets investors, such as those focusing on distressed opportunities amid the current extraordinary global economic slowdown.

COVID-19 has hit global economies with a sledgehammer and

prompted investors in the private markets field – debt, equity,

infrastructure and property – to fret about valuations to

existing assets and wonder if they can snap up opportunities.

The term “vintage” – applying to the year when an investment was

initiated (like when a grape is harvested) – may be looked at

particularly closely in future if managers can buy assets on the

cheap. Those funds that were “bottled” when markets were on the

floor might hopefully taste wonderful as and when there is a

recovery. (Of course, as any serious wine collector knows, it is

wise to hold a range of vintages rather than shoot for the

“perfect” one.)

Another feature of virus-roiled markets is that some funds that

had thought of closing their doors to new money might open up

again in the current environment.

That is the view of Heather Jablow, managing director, Private

Client Practice, and Philip Walton, managing director, Private

Client Practice, for Cambridge

Associates.

“Prices are dropping and should create opportunities in a number

of areas,” Walton told this news service. For example, technology

and healthcare sectors are worth examining given their growth

potential. On the flipside, he said, there are also some

distressed investing opportunities in parts of the cyclical

manufacturing sectors.

Cambridge Associates provides investment services to

organisations and private clients including endowments and family

offices. Unsurprisingly, the team is busy.

An ever-present area of work is monitoring clients’ liquidity

needs, as well as tracking distributions from investments, calls

for capital, and tax payments, Jablow told this news

service.

As private markets investing is typically far less liquid than

for, say, listed equities or cash, such close monitoring of

clients’ liquidity needs is particularly important. “It is

critical to understand and plan for liquidity needs in both

normal markets and in stressed markets, when the circumstances of

clients may change,” she said.

The distressed players are on the move. According to the Wall

Street Journal (3 May), Apollo Global Management plans to

raise money to capitalise on demand for loans during the

coronavirus pandemic. The US firm expects to raise $20 billion

over the coming year, emphasising credit strategies designed to

take advantage of economic dislocation.

Private-equity firm General Atlantic is teaming up with veteran

credit investor Tripp Smith to launch a roughly $5 billion fund

(WSJ, 14 April). Such operators, also nicknamed perhaps

unfairly as “vulture funds”, typically target assets trading at a

significant discount, and restructure a business to pocket a

profit. While they can be attacked for exploiting tough times,

arguably they are vital to a free market system where capital can

be put back to profitable use rather than fall idle.

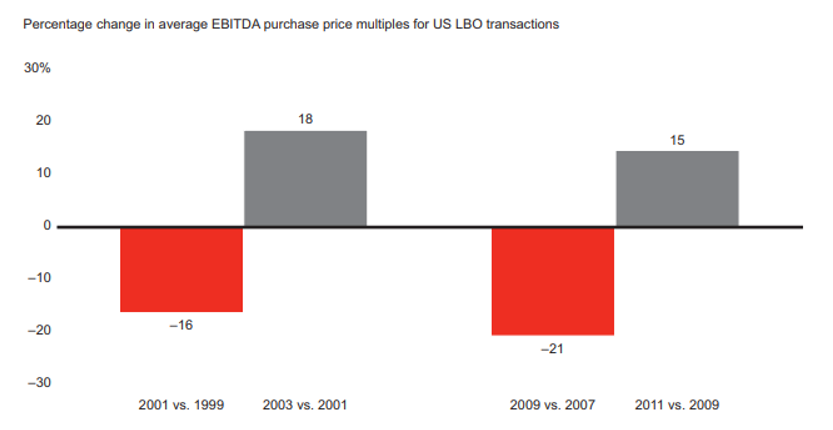

Distressed investors have to move fast. According to a report by

Bain & Co, in the past two downturns, the average leveraged

buyout purchase price multiple sank by about 20 per cent from its

high but then recovered most of that within two years.

Source: Bain & Co

Under pressure

“There will be a lot of distressed assets coming up for sale,”

Olamide "Lami" Ajibesin, who leads transaction advisory for

Anchin,

Block & Anchin LLP, a public accounting firm in North

America, said. She advises private and public clients on M&A

and PE transactions (including secondaries) and strategic

investments in energy (E&P/oil and gas, power), consumer

products, industrials, financial services and technology, among

other industries.

Among areas hit by the pandemic that could lead to opportunities

include aviation, luxury and travel, she said.

Ajibesin works with family offices and others, both on the

institutional and non-institutional side. The pandemic has raised

a few challenges, such as being able to conduct due diligence on

investments, although she was already used to working remotely

and handling a number of processes via that route.

Private markets investment funds collectively hold a lot “dry

powder” – money not yet put to work. At the end of 2018 there was

$2.0 trillion of private equity spare money globally (source:

Bain & Co, 2019 report). Fast forward to the coronavirus-blighted

spring of 2020 and a lot of that money could be put to work. But

investors are not going to be in a hurry, given uncertainties for

some time to come, said Ajibesin.

“The mood of investors now is more introspective….people are

taking their time,” she said.

As the cited Bain & Co report, issued over a year ago shows, the

industry was if anything concerned about an overheating, fiercely

competitive private markets sector. A decade of ultra-low

interest rates and frustration over weak bond and tight equity

yields has encouraged a flood of money into the private

investments space. In the past few weeks, however, the pace of

fundraising into private equity has slackened. A few days ago,

research firm Preqin, polling 183 private equity firms in April,

found that well over two-thirds of them (69 per cent) said their

fundraising had been hit by the global pandemic, and a third (32

per cent) said it had significantly slowed.

Private market industry figures hope that medium- to long-term

data will remind people that it makes sense to stay on board for

the long haul. According to Cambridge Associates, its US Private

Equity Index (Legacy Definition) chalked up 25-year returns (as

of 30 September 2019) of 13.35 per cent, ahead of 9.83 per cent

for the timespan at the S&P 500 Index of US equities. That

“gap” perhaps explains so much of why private investing remains a

hot favourite with wealth managers.